Interview: Wakae Nakane & Miryam Sas (1990s Experimental Film in Japan: Women’s Anarchic Visions of the Everyday)

Hello and welcome to Rep Cinema International. Today’s interview is with Wakae Nakane & Miryam Sas, co-programmers of the recent screening 1990s Experimental Film in Japan: Women’s Anarchic Visions of the Everyday at the Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive in California. I noticed this screening (among the PFA’s generally excellent programming) because of the rarity of the films/filmmakers included and the obviously huge amount of research that went into composing it. Not to mention that the images look so enticing as well! I decided to ask the co-programmers more about the program and their research into this particular area of experimental film made by women in Japan. I hope you enjoy our conversation.

Thank you both for speaking with me. Could you introduce yourselves and give some background on your wider research?

Wakae Nakane (WN): Thank you for giving us this opportunity. I am a PhD student in Cinema and Media Studies at the University of Southern California. My research interests include Japanese documentary and experimental film, feminist film theory and historiography. Female authorship in non-commercial filmmaking is one of the topics I’ve long been interested in. I wrote my master’s thesis on women’s self-representation in documentary film, and I am currently working on my dissertation project which expands the scope of the study into the wider appearance of essayistic cinema in independent filmmaking in Japan since the 1970s.

Miryam Sas (MS): I’m a professor of Comparative Literature and Film and Media at UC Berkeley, and my research encompasses avant-gardes and experimental arts from the 1920s to the present. My first book was about Japanese surrealist poetry and manifestoes, and the second one was about the Japanese arts (underground theatre, photography, film, dance) of the 1960s-70s. My forthcoming book (Feeling Media: Potentiality and the Afterlife of Art, Duke University Press, 2022) reads those arts of the 1960s-70s and their legacies in the contemporary art of the last 20 years, with a special interest in intermedia art, media theory, and photography. The relationship between intermedia art and contemporary media art is very tight, but could use a lot more theoretical reflection and recognition. There’s a strong focus on women artists in the last half of that book.

I'm really fascinated by your program “1990s Experimental Film in Japan: Women’s Anarchic Visions of the Everyday” which screened recently at the Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive. How did you research and conceive of this program?

WN: Our collaboration started when Miryam generously offered me an opportunity to co-curate the program featuring female artists in the Japanese experimental film. We initially started to look at women’s participation in cinema-making in Japan across the wider-range of independent filmmaking that encompasses documentary, animation, and experimental films from the 1970s to the 2010s. It’s a continuation of my archival research that I had conducted in Japan before coming to the US in 2019, and film viewing at various film festivals including Image Forum Festival, Pia Film Festival, and Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival. So, I started by contacting filmmakers I knew asking about the availability of their works for preview.

MS: Thanks to Kathy Geritz at Pacific Film Archive, with whom this fall I co-curated the Alternative Visions series that screens along with a survey course on experimental film and media at Berkeley, Wakae and I were able to have a ready venue for these works. I knew that I didn’t just want to teach the students the history of Euro-American experimental film and media—I wanted to include works from Japan, Brazil, and beyond as well as adding much complexity to the limited racial imaginary of how this course was conceived even as recently as 2004 when I taught it last. But to do so we needed to make our own programs.

WN: Archival projects and research are gradually shifting their attention to independent film in Japan, but there are no comprehensive archives at which we can delve into women’s image-making. However, Image Forum (1972–), and Pia Film Festival (PFF, 1977–) are the two core institutions that have served as a ground for women’s participation in filmmaking, especially since the 1980s. We contacted both, and we learned that PFF has been proceeding with the five-year large-scale plan of digitizing the materials that they store. As it was more difficult to ship celluloid materials for our review within the limited amount of time, we saved these materials for future screenings. Kenji Kadowaki from Image Forum gave us consistent support in helping us get in touch with filmmakers and making previews available for some works by digitizing them and sharing them with us. He put a lot of effort into tracking down the contact information of some of the more difficult to reach filmmakers.

What decisions went into deciding which filmmakers and specific works you wanted to show in this screening? What are your relationships with these filmmakers like and do they distribute their own work?

WN: The initial plan that we submitted to Kathy Geritz encompassed a wider range of timelines from the 1970s to 2010s, including filmmakers from different generations.

MS: I was really eager to include Michiko Sasaki’s To Die Sometime (Itsu ka shinu no ne) (佐々木美智子『何時か死ぬのね』) (1974)—check out this program at the TOP museum in Tokyo in which it was included—and to do a whole survey of women’s participation from the 70s, including Sonoko Ishida, Mako Idemitsu and beyond. But that’s often my period of research so I guess it makes sense that I’d want to work in that era.

WN: That original sketch also included a diverse range of expression, from film experimentalism to lyrical documentary works. However, consultation with Kathy made us think that it would be better to narrow down our focus and scope to create a more coherent single program, and then save the others for another time. We decided to focus on the 1990s, an era that saw a burgeoning participation of women filmmakers working in the Japanese experimental film scene. We also wanted to create thematic threads among these works, so that the program will have a more coherent focus, while showing the diverse range of styles and aesthetics of each filmmaker, which cannot be reduced to a monolithic category or style. I’ve seen these filmmakers’ works (except for Yūko Asano’s animation works) previously at various film festivals and through archival research at Image Forum, but this is the first time for me to collaborate with them directly. I had contact with Utako Koguchi after meeting with her at an event in Tokyo titled Memories of 80s Independent Films organized by Yōko Oguchi, an important figure in independent filmmaking who has been actively creating her own works since the 80s. However, we were mostly reliant on Kadowaki-san to get us connected with the other filmmakers. For Yūko Asano, the Japan Animation Association helped me to get in touch with her.

MS: Wakae did great work creating this network.

WN: We ended up choosing works that share a tendency to foreground narrative rather than abstract experimentalism. Although experimental films are often aligned with non-narrative filmic exploration, the presence of the narrative in each film doesn’t mean that they are not experimental. I think each work in this program is still highly experimental in a way that diverts itself from the narrow definition of experimentalism by actively embracing an anarchic or playful treatment of narrative with a surreal sense of irony. Also, I think another feature of many of the works from this period and some of the works in this program is the interest in the representation of corporeality, and interrogation of the status of the body alongside the meditation on the ritualistic nature of the everyday private/social activities. The interesting thing is they are not naïvely essentializing the body, but they show more sophisticated meditations on its materiality and performativity.

For instance, Hiromi Saiki’s work deals with the fictions of reality and the self by placing her own body at the center of her examination of the theme of social alienation that was a pervasive phenomenon in 1990s Japan. The anxiety of contemporary identity crisis and the fear of isolation is represented through the physicality of her own body and her consistent anxious voiceover. It also shares with other works the meditation on the ritualistic nature of the everyday where we are subjugated by excessive self-consciousness, as Yuko Asano’s stop-motion animation film, The Life of Ants (1994) meditates on the prevailing power dynamics in human society, and how we are subjected to it through ritualized activities.

MS: Saiki’s work is so resonant, the way it repeats the words “Kasetsu” (Hypothesis) and reads or observes the self as a kind of data, through the medium of things like direct mail that the central figure receives. She also thinks through the process of mediation and the gaze by foregrounding video within the film and layers of framing. (This work that we showed, called The Place which Isn’t Necessarily Wrong (Anagachi machigatteru tomo ienai kū) (才木浩美『あながちまちがってるともいえない空』) (1996), could also be translated/read as “sky” rather than “place” but the filmmaker wanted it read and translated this way. It’s an advantage that you can ask the filmmaker directly.)

WN: There is not a thorough distribution network for experimental cinema like Canyon Cinema in the US, or for films created by female artists like Women Make Movies. For that reason, we corresponded with each individual filmmaker to gain access to their works for the preview, and with some filmmakers, Kadowaki-san helped us by transferring the analog files such as VHS into a digital format so that we could view their works. We learned though that there are some distribution labels for these non-commercial experimental works such as Kuraut Film, that helped newly digitalize Yuko Asano’s work and send the digital file to BAMPFA. It seems that they also proceeded with digitizing Asano’s other works.

Could you speak about the conditions and infrastructure that led to this rise in women's experimental film in Japan during this specific period?

WN: A surge in women’s participation in experimental filmmaking took place starting from around the late 1980s to the early 1990s in Japan. It was associated with the increased availability of film equipment and the wide-spread establishment of film schools and various film festivals such as Image Forum and Pia Film Festival. Image Forum has particularly served as a major hub for experimental filmmaking, exhibition, and distribution from the late 1960s up until today. In regard to female authorship, it has functioned as an important venue for them to collectively discuss and publicize their work through their writings and the exhibition of their films at the Image Forum Film Festival. For instance, we can see the dramatically increased number of participants in the exhibition at their annual film festival around that time. Also, once you look at Gekkan Image Forum, which is a monthly journal published by Dagero Publishing from 1980 to 1995, there are a lot of issues and articles featuring women’s participation in experimental filmmaking, especially since the late 1980s.

MS: Maybe we should translate some of those to give some more context to these works and the debates around women filmmakers that they evoke, one day. Questions around the use of the body (the use of nudity in one’s own film, for example), the reception and openness to films by women directors, etc.

WN: In terms of the educational infrastructure, at schools such as the Image Forum Institute of the Moving Image, Tama Art University, Musashino Art University, Kyoto College of Arts, there was a big influence from the previous generation of (male) filmmakers, who were pioneers of some leading trends in independent filmmaking starting in the 1970s. Some of these filmmakers are luminaries of the strand called private film (puraibeto firumu), which is conditioned by a more individualistic style of filmmaking accentuating personalized artistic visions, such as Shiroyasu Suzuki, who had taught at Tama Art University and Image Forum Institute of Moving Image, and Nobuhiro Kawanaka, a founder of Image Forum, who also taught there.

MS: You can’t really look at the work of the women filmmakers in isolation from those trends and works. Their politics is intimately imbricated with those earlier works.

WN: This infrastructural change led to the rise in women’s experimental film in terms of its expanding of the chances for participating in filmmaking whose masculine logic of collectivity had oftentimes excluded women from the creative realm. For instance, Hiromi Saiki learned filmmaking at the Image Forum Institute of the Moving Image. Yukie Saitō began making films as a student at Tama Art University, where she studied with Utako Koguchi, who worked as an instructor at that time. Koguchi later became Professor at Musashino Art University and has been playing a role in shaping Japanese independent film. Yūko Asano also works as a lecturer at Musashino Art University. Mari Terashima started her filmmaking in the 1980s at Kyoto Collage of the Arts, where she was trained by artists including Toshio Matsumoto, who is one of the most prominent experimental media practitioners in postwar Japan.

In their focus on "anarchic visions of the everyday", do these works share elements of form and/or content with other international makers or movements in experimental film? Do they correspond with any other contemporaneous women's movements in Japan?

WN: As far as I know, there was not very active international collaboration or communication among filmmakers in this period compared to the previous decades. In contrast with the filmmakers’ community in the 1960s and the 70s, when experimental work from overseas was actively shown and introduced, and we can point out more direct correspondence among international makers, the 80s and 90s saw that the correspondence became a bit more ambiguous because of the less frequent showcasing of international experimental films contemporaneously.

MS: I’m not sure I agree with you there—I think in the 1990s, whether or not there was direct collaboration by these filmmakers with international artists, there were a lot of chances for exposure to Euro-American experimental film works—both at the schools and in the broader film venues like Image Forum. Right?

WN: Definitely, we can find shared elements with other international makers. The anarchic visions on the ritualistic nature of life and the corporeality of the body have been one of the central themes of a lot of feminist experimental filmmaking. They include highly influential works of Maya Deren, and multi-media experimental works of Carolee Schneemann, and so forth. More contemporaneously, their works share the claustrophobic distortion of familial space that was popularized through Sadie Benning’s series of experimental personal films.

MS: The queer energy in Yukie Saitō’s The Night When Water Comes Down (1992)—even if the two women are supposed to embody aborted twins according to the intertitles, their intimacy and way of moving through urban space, their anger with the nuclear family system that excludes them—links that film in some ways with trends in queer cinema in the 1990s. The gender ambiguity in the lengthy and claustrophobic Midorimushi (Green Worm, Mari Terashima) and (violent) gender performativity was one of the elements of that film that charmed PFA curator Kathy Geritz and made her want to include it in the program, in spite of the challenges it posed to the audience in terms of duration.

WN: The late 1980s and 1990s signals some essential moments when the legacy of the Women’s Liberation Movement (Ūman ribu) in the 1970s came to fruition within several institutionalized frameworks. More and more universities and colleges started to have departments or schools specializing in Women’s Studies or Gender Studies, and the first Equal Employment Opportunity Law became effective in 1996. Although that progressive appearance oftentimes has contradicted the reality and the persisting legacy of patriarchal misogyny that is still pervasive throughout Japanese society up to our contemporary moment. However, at the same time, the diminished practice of the street politics such as Ūman ribu, which had its peak in the early to mid-70s, made it more difficult for women to engage collectively in the societal challenges in the 80s and 90s. In this sense, it is difficult for us to draw a strong correspondence between these works and the contemporaneous women’s movement, considering the absence of strong centrifugal power of feminism outside the academic realm at the cultural and societal level.

Meanwhile, the surge of identity politics that started encompassing the realm of LGBTQ movements became active worldwide around this time. 1980s Japan still saw some related movements and establishment of organizations, but they have not yet reached the level of social prominence and political success as similar groups in the United States and Western Europe. Although this is not shared by all the works we featured, like Miryam said, some of the works address the issue of gender and sexuality corresponding to the ambient atmosphere of this period. Utako Koguchi’s A Dandelion, Rosaceae (1990), a playful film that explores the issue of the ambiguousness of sexuality by queering the relationship between the body and the voice, is a rather indirect meditation on the worldwide AIDS crisis in the 1980s.

You describe the prior decades of experimental film in Japan as being "almost exclusively male". Are there any notable exceptions of women filmmakers working in earlier eras in Japan?

WN: There are some influential figures such as Yoko Ono, Mako Idemitsu, and Fujiko Nakaya. For Idemitsu’s works, we can see a stronger articulation of feminist politics that is directly associated with the postwar feminist movements.

MS: We considered Sonoko Ishida for the program because of her abstract and structural films. But in the end she fell outside our time period.

Finally, how was the screening at BAMPFA? Do you have any plans to screen these films elsewhere or further develop the research?

WN: We were discussing serializing this event as we have encountered very rich archival resources thanks to the generosity of each filmmaker, but unfortunately we couldn’t include everything in this program. I’d love to screen this specific program again at some venues if it is allowed. I am also currently seeking some opportunities to show their works in Los Angeles as well, as I think, in addition to San Francisco, it is another place where we see the strong presence of filmic experimentalism contrary to the impression of the city as being exclusively the domain of Hollywood.

MS: It is likely that this program will be streamed in March 2022 or after at CCJ (Collaborative Cataloguing Japan). We were just discussing that possibility this morning. I hope it will happen!

Thanks again, Herb, for inviting us to share these thoughts with you today!

Endnotes

Thank you to Wakae Nakane & Miryam Sas for speaking with me. Their program “1990s Experimental Film in Japan: Women’s Anarchic Visions of the Everyday” took place October 20, 2021 at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive in Berkeley, California. Here’s wishing them the best with continuing to showcase this research in screening form, as it sounds like there is a lot yet to be shown.

Since they were mentioned at the end of the interview, I’d like to extend an extra recommendation for Collaborative Cataloguing Japan for the great work that they are doing in this area as well. I am a member of their monthly screening room which provides access to rare works of Japanese experimental film and you should be as well!

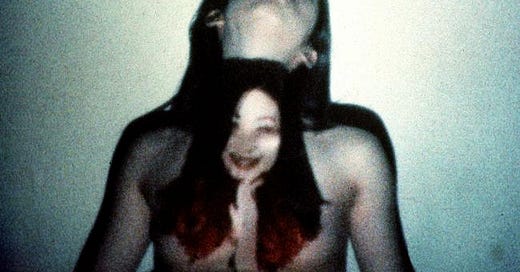

Images: The Place Which Isn’t Necessarily Wrong (Hiromi Saiki, 1996) // A Dandelion, Rosaceae (Utako Koguchi, 1990) // The Life of Ants (Yūko Asano, 1994) // Green Worm (Mari Terashima, 1991)

Thanks for reading! Subscribe if you’re coming to this from the website and please share if you find this useful. While the main channel is this Substack newsletter, you can also find Rep Cinema International on Twitter, Instagram and in list form on Letterboxd.

Questions, comments or other inquiries: RepCinemaInternational@gmail.com