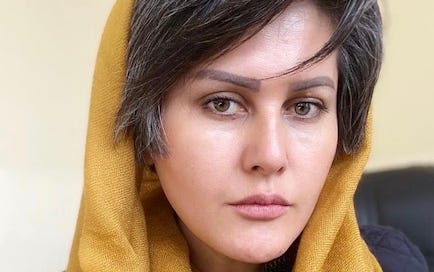

Interview: Sahraa Karimi (Afghan Film)

Hello and welcome to Rep Cinema International. An important part of this publication is interviews with programmers, archivists, distributors and many more—people from around the world who help repertory and archival films to the screens.

I’m excited to share today’s very special interview with Sahraa Karimi, filmmaker and Director General of Afghan Film, the country’s state-owned film production company and archive. After earning a PhD from the Film & Television Faculty at the Academy of Music and Performing Arts in Bratislava, Slovakia, she moved back to Afghanistan to make films in her native country. Her most recent feature Hava, Maryam, Ayesha (2019) was an official selection of the Venice Film Festival, Mill Valley Film Festival and Busan International Film Festival.

We spoke about the Afghanistan’s cinema history, the current state of its cinema culture and the new generation of filmmakers showing it’s possible to make films in Afghanistan today.

Thank you Sahraa for speaking with me. Could I ask you to introduce yourself and give us a bit of your personal background?

Sahraa Karimi (SK): I am a film director and current Director General of Afghan Film, a stated owned production company. I studied film directing at in Slovakia and belong to the new generation of Afghan independent filmmakers.

As a filmmaker, you've directed over 30 short and feature films, both documentary and fiction including the Venice-premiering feature Hava, Maryam, Ayesha (2019, Afghanistan). Could you describe your filmmaking style and speak about your particular focus on showing the lives of women in Afghanistan?

SK: In 2003, when I wanted to do my entry exam for film directing at FTF-VSMU in Bratislava, Slovakia, they just opened documentary film directing in that year. First I entered the documentary film department and the next year I joined the fiction film department. So this documentary style of storytelling stayed with me. For example, I prefer to have non-actors in my film. I don’t like reconstruction or very much re-building of locations, I prefer to go to a real location. In Hava, Maryam, Ayesha, for Hava’s part I rented a real home of an ordinary family in a part of the city in which the style of living was in the way that I wanted. So I didn’t need very much to add props or any kind of special color.

I am also very much under the influence of Eastern European cinema: Slovakia, Czech Republic, Poland, Hungary. You can see these influences in Hava, Maraym, Ayesha, in the very long shots, the camera movement or the main thing, the colorization of the film. I also really love old Japanese and Chinese cinema. It is my habit before any new shooting to watch my very favorite films or to go to a very different location of the city and start taking pictures.

I am still not very mature in my filmmaking style, but you can notice the character of my filmmaking from even my student film. For me is very important to tell the story in a way that I feel connection with; I don’t like very much to push to very unique style or to push very much to copy some master’s style.

I've heard that Afghans really love cinema. What is the cinema-going culture in the country like and do you have any favorite cinemas? I'm also curious if you have any thoughts on I-Khanom Cinema (Lady Moon Cinema), referred to as the country's first woman-focused cinema.

SK: Of course Afghans love cinema but unfortunately the system and people themselves they didn’t do anything for development of this LOVE. Once upon a time in Kabul there were around 32 cinema halls and going to cinema was part of the social culture. But during the civil war and Taliban regime everything was destroyed. Now we have just two cinemas in Kabul which are in very bad condition and belong to the municipality. In the provinces we don’t have any cinemas. It is real tragedy for filmmakers and our society that in the 21st century, in the era of technology, we don’t even have one single proper cinema in Afghanistan.

About the I-Khanom Cinema: it is just a very small film club, it is not cinema with proper technology. I am not very sure about “the country's first woman-focused cinema”? It is normal film club and with very limited seats and unfortunately they screen films without copyrights. But we are happy they opened. Even this very small cinema club may help others to go ahead and open a bigger cinema.

In addition to your own filmmaking, you've made history as the first woman Director General of the Afghan Film Organization. Could you sketch a short history of Afghan Film and describe where it sits within Afghanistan's cinema history?

SK: Yes, that is correct. Afghan Film opened in the late 1960s with help from the United States and went on to oversee the production of movies across Afghanistan over the following decades. But when the Taliban took over the government in Kabul in 1996, the militants enforced a strict version of Islamic law, banning music and moving images. So Afghan film didn’t produce any film during the Taliban regime.

Over the past 18 years [since the Taliban regime fell] there was potential to rebuild Afghan Film, but unfortunately previous managements didn’t do any significant projects or make any plans for this state owned production company that were a great help for Afghan filmmakers. It was very active during 1960s but after that it hasn’t been very active.

When the government decided to change the management, they publicly announced the position of Director General. So I won all the exams and got the position. Ive been here almost 8 months and try my best to make significant changes, but it is not easy.

Afghan Film has been heavily invested in safeguarding Afghanistan's cinema history, notoriously hiding thousands of film reels from the Taliban. How does the organization advance this mission? Could you describe the archive's process of digitization?

SK: The Afghan Film archives is one of the biggest in the region and it is very rich archive. Unfortunately during these past 18 years the previous managements were very careless about this very important department of Afghan Film. Before I joined Afghan Film, the government and the ARG Archives department, which is under president’s office, decided to take all the Afghan Film archives to the ARG Archives. So these films legally belong to Afghan Film but are is under control of ARG Archives. So we don’t do any digitalization here in Afghan Film. All process is running under ARG Archives Department.

Though it's been difficult for me to access much Afghan cinema, I've found this collection of digitized reels on the pad.ma website. They show newsreels and feature films from between the 1940s and 1990s. Can you somehow characterize the films which were produced by Afghan Film and what is found in the collection?

SK: Most of the movies and films were not digitalized, and unfortunately some archives got out side of Afghan Film illegally. During the 1960s and the Soviet Union time in Afghanistan, Afghan film and its board of directors produced the most famous films. These were comedies, melodramas, war films and mostly propaganda films. But the quantity was high. Unfortunately the war started, many of those significant filmmakers decided to immigrate and there was a time when nobody was able to make even a one-minute short film.

Mostly they shot with 35mm cameras and people used to go to the cinema and the film market was very active. Even Bollywood films were very popular among Afghan people, but still Afghan Film produced films that attracted thousands of people. There was even a black market for getting tickets for newly-released films.

I'm interested to hear about the film festival held in August 2019 to celebrate 100 years of independence. It's written in Daily Sabah that 100 mostly classic Afghan films were shown, and that 13 features in particular were digitized and shown. How was this festival programmed and what was the response?

SK: I joined Afghan Film at the beginning of June 2019 and I heard that our government is going to celebrate 100 years of independence in August. I spoke with authorities and proposed we have a pure Afghanistan Film Festival and show 100 films, because during these last 18 years people almost forgot about going to the cinema. And I decided to also show films from the old times and there were just 13 fiction films that have been digitalized.

It wasn’t very easy because we had a very short time and I was also very new in Afghan Film, and not very familiar with government paper work process which is just a killing process. But we did it and it made big headlines for the media. People really welcomed the idea. We sold almost 5,000 tickets during the 8 days of the festival, which was a very important number for Afghan cinema. Even for some films like Epic of Love (Latif Ahmadi, 1989) people were standing in line. So for me and my team it was a real happy moment seeing how people wanted to see our own Afghan films so much.

What are your particular favorite Afghan films both classic and contemporary? Are there titles and filmmakers you'd recommend cinephiles unfamiliar with the country's cinematic history seek out?

SK: From classic films, I really like Bigana (Stranger, 1987) by Siddiq Barmak. From the contemporary films, I really like Earth and Ashes (2004) by Atiq Rahimi.

I think the new generation of filmmakers who were immigrants or studying outside of the country are making good films these past 2–3 years. Their films are shown in programs of the most important film festivals and I believe there is a new movement. So any film that gets a chance to be shown in film festivals or cinemas and is from Afghanistan, I am sure is a good one. So I recommend to watch all films that Afghan filmmakers have made during past 5 years. All of them are great.

Does Afghan Film loan prints and/or digital copies of films from the archive for screenings?

Yes. We just recently opened the distribution department of Afghan Film so we can easily provide our films specially from archives, and we even can make MoU agreements with film festivals or distributors too.

As a filmmaker and head of Afghan Film, how would you describe the culture of filmmaking in Afghanistan today?

It is very hard, because many film production companies outside of Afghanistan don’t believe that it is possible to make a film inside Afghanistan. Also, we don’t have a real and professional film production company inside Afghanistan. And the views about Afghanistan and its stories are very cliché, so if you want to convince a producer to invest in and to produce a film inside of Afghanistan, you need to go through a very hard and long process. And even this doesn’t guarantee that the producer will support you through the end of the production.

But my film Hava, Maryam, Ayesha has been made entirely inside Afghanistan and was the official selection of Venice Film Festival, so it shows that we can shoot and make films inside Afghanistan. We have unique stories which can break the market too, we just need big production companies to trust Afghan filmmakers. Afghan Film is ready to cooperate with all film companies around the world. We need to change the narrative about Afghanistan and I deeply believe it is possible through cinema.

Endnotes

Thank you very much to Sahraa Karimi of Afghan Film for speaking with me. You can follow @sahraakarimi on Twitter and Instagram.

The featured images in this newsletter are the beautiful vintage Afghan Film logo, gif’d from this newsreel film; Epic of Love (Latif Ahmadi, 1989); and Earth and Ashes (Atiq Rahimi, 2004).

More info on upcoming interviews will be coming soon.

Thanks for reading Rep Cinema International. Subscribe to get this newsletter directly sent to your inbox. While the main channel is this Substack, you can find Rep Cinema International on Twitter @RepCinemaIntl and on Instagram @RepCinemas. I’ve also made a list of featured films on Letterboxd.

Questions, comments or other inquiries: RepCinemaInternational@gmail.com.