Interview: Abby Sun & Keisha Knight (My Sight is Lined with Visions)

Programmers of the online series charting an alternate history of Asian American independent film and video

Hello and welcome to Rep Cinema International. I hope you’ve all been safe and doing well. I’m going to start grinding the gears together and bringing this newsletter back to life and thought the perfect way to restart would be talking about an exceptional online repertory/archival film series launching today.

My Sight is Lined with Visions is a landmark series of 1990s Asian American film and video, bringing together a number of works showing different forms, ideas and perspectives. But these films and videos are united in their goals to not only break cultural stereotypes of Asian Americans but also to break the tropes and conventions of dominant forms of cinema, media and art. They’re also at turns gritty, sexy, engrossingly entertaining and wildly experimental.

I spoke with the series programmers Abby Sun—a filmmaker, photographer and programmer—and Keisha Knight, co-founder of Sentient.Art.Film, a creative distribution initiative through which the series is hosted. My Sight is Lined with Visions runs from May 29–June 7 and is available for rental on a tiered pricing scheme, has a selection of free-to-watch short films, essays by Asian American critics and two Q&A events as well.

Thanks Abby and Keisha for speaking with me about My Sight is Lined with Visions. Could you tell me about the genesis of this project and what you hope it could contribute to both culturally and film historically?

Abby Sun (AS): Thank you, Herb, for speaking with us! The spark that really got us going was a phone call from Keisha to me. She was the one who thought this was possible, and I was energized by that. This is important because we have thought just as much about the technical backend of this series as its forward-facing aspects like the essays, the Q&As and the publicity plan.

Previously, we had collaborated on moving a one-off screening of Miko Revereza’s No Data Plan (2019) as part of the DocYard, a biweekly nonfiction series I program at the historic Brattle Theatre in Harvard Square, online. We did this the week after the state issued a shelter in place order and the Brattle closed, and after we had an intense conversation about whether filmmakers are reliant on larger distributors for streaming and educational distribution (we had no idea about the “virtual cinema” craze that was coming).

May was supposed to be a big month for Asian American film, as it always is, being Asian/Pacific American Heritage Month in the US, and we all know how hard it is to get coverage of anything if there’s nothing to “peg” it to. I had been tracking closely the landmark PBS series Asian Americans. (There’s a connection with this series there—one of the producers and co-directors of Asian Americans, Grace Lee, worked on both Strawberry Fields (Rea Tajiri, 1997) and Fresh Kill (Shu Lea Cheang, 1994)!) I also knew that Chi-hui Yang had curated a series at BAM focusing on Asian American cinema in the 90s and the aughts for this past month. Though Asian Americans was successfully released earlier this month, we got confirmation that the BAM series is postponed indefinitely, for now. But, during the pandemic, with Asian American film festivals moving online for this month, and with lots of media coverage of the sharp rise of anti-Asian racism in the US, we saw a space for nimbly and thoughtfully assembling a repertory program about how gloriously messy and punk Asian American film really can be.

Culturally, what we’re responding to is the decades-old idea of representation being the thing that matters. What this focus elides, often accidentally, is everything that came before. At the same time institutions like Visual Communications and CAAM (originally the National Asian American Telecommunications Association) were founded out of the Asian American Movement, artists like Nam June Paik, Yayoi Kusama and Yoko Ono were making work in NYC. Similarly, now, I think about how A24 has embraced Asian American filmmakers like Lulu Wang and Lee Isaac Chung, and how formerly indie filmmakers like Justin Lin have achieved massive international success—and, at the same time, some of the biggest American Youtube stars and Twitch streamers are Asian American. Though they’re dependent on some of the biggest multinational corporations in the world for their platform, the work is far more independent in a business sense. There’s also the issue of continual anti-Blackness in Asian American communities, and the pandemic is, like everything, showing the weak spots in our belief systems on this front. Because of all of this, I, like many others who are visibly Asian (American) feel an urgent burden to complicate media narratives. To me and to Keisha, though, just as important as the idea of there being more “born again Asians,” meaning that many Asian Americans politicize in adulthood, to use Richard Fung’s words, is the voracious support of films that are formally and politically radical enough to help us make sense of this world, both personally and systematically.

For this series, we hope to weave together all of these threads in terms of the conditions of production and distribution, instead of focusing on putting together the most representative program--itself a tall order for a two-woman band. It’s also perhaps a project that is destined to fail by playing into the urge to catalog and thus make imperialist order of a world that already is deeply unequal and becoming more so. We saw film institutions failing daily around us. We are both former film festival programmers and know very well the positive and the negative effects of that system on sustaining the film industry. For My Sight is Lined with Visions, we dreamed up everything we wanted, seeking inspiration from series, festivals and projects we’ve admired in the last few years.

The film and video works which you're highlighting from Asian American artists are all pushing boundaries in different directions. You've said the selection represents an "alternative history" of Asian American film and video, so I wonder if you could explain your view of the standard history and how these works depart from it?

Keisha Knight (KK): So, for me, standard film history is often an object oriented story that tends to privilege content over process. What I mean by this is that the film object is narrativized for some inherent truth value that exists in the vacuum of the frame. Politically engaged filmmaking practices are often sidelined or boxed off and filmmakers are forced to choose between the aesthetic camp or the political camp. That’s what is so exciting about the films in My Sight is Lined with Visions: the filmmakers are all resisting the boxes.

“Toward a Third Cinema” is one of my favorite film texts (along with Glauber Rocha’s “The Aesthetics of Hunger”) because it is one of the few texts that understands the enmeshment of objects and systems (i.e. the film cannot be separated from its production and distribution). This is actually something that Abby and I both think about a lot: How do films move? Who is deciding where the boundaries are? Why are the bodies of people of color suddenly appearing in tentpole movies? Is this anything new?

The process of historiography is also a type of circulation and mythmaking which often, like much of the profit driven universe, is dependent upon not looking back and not questioning received mythologies: the inevitability of progress. What we’re calling an “alternative history” is less about objects per-se and more about energies. Bear with me… alternative history is not interesting as a fetishized, fossilized, nostalgic token. “Alternative histories” are only interesting in that they help us imagine alternative futures. The word “alternative” is a bit of a language trap. This program really represents a kind of possible history to help us imagine possible futures which allow the generation of films that don’t simply put the bodies and lives of people of color on the conveyor belt of object-oriented profit but rather spark and dance and dare to probe reality in whatever ways feel right.

Another “alternative,” or possibility, that we’re trying to create and enact with this screening series is developing direct artist-to-audience ways of supporting creators. With the filmmakers we work with directly who have ticketed programs, we are splitting all ticket sales with them 50/50 (after the Vimeo admin fee, which is unfortunately higher than we would like). We recognized that many young film critics are freelancers and their work was drying up, and that they didn’t often get a chance to engage with repertory titles, and that there are other indices of knowledge production and engagement beyond ticket sales. If we can create a real engagement with these ground-up online projects it can mean a lot to filmmakers and to initiatives like Sentient.Art.Film trying to make space for visions that don’t tick the boxes (or tick all of them backwards and upside down).

Really figuring out ways that we can directly support artists and art-making is essential to shifting that conservative taxonomical mindset that tries to put audiences and films into boxes and then starve them of anything but mediocre content. This is really serious. The constriction of our imaginations (by greed [profit first] and fear [no one will like it] and laziness [too hard]) is the constriction of the futures we can imagine. It takes all of us together, audience, exhibitors, filmmakers and distributors to create a different, more dynamic film ecosystem. Film is not just cultural-object but also cultural practice.

Can you describe the research that went into selecting the films and videos which you're showing in the series? Were you working with archives, distributors or filmmakers directly?

KK: Abby and I can talk to each other for hours on end. We literally have 3-hour phone calls! We started the selection process by just talking through different permutations and what the intervention/offering of the series could be. We both already had relationships with filmmakers who we thought would be good fits for the program so we reached out to them and gauged their interest then built the program out from there.

Sentient.Art.Film was co-founded with producer Sarah Kim. One of our main aims in starting the initiative was not only to create space for new work but also to bring more visibility to repertory works that may not have gotten the attention they deserve. Sarah and I were actually in conversation with Shu Lea Cheang in the summer of 2018 to see if she would be interested in having us work on a re-release of Fresh Kill for the 25th anniversary. The project didn’t come together but getting Fresh Kill in front of a wider audience has been on my mind for awhile. I’ve been working with Roddy Bogawa since last spring when he agreed to have us distribute his work and he’s been amazing. Last summer Roddy connected me with Jon Moritsugu. They’re both incredible, super generous and always up for new things. They’re both really inspiring people.

I met Spencer Nakasako recently through Miko Revereza. (It was actually after receiving an email from Spencer that the idea of the streaming series was born.) Again, another incredible soul… notice a trend? Abby knew Rea Tajiri, another generous and beautiful person, and connected with her. We worked with Video Data Bank and Women Make Movies for filmmakers we couldn’t connect with directly or for those who preferred us to go through a distributor but we tried to organize directly with filmmakers if at all possible.

An interesting part of this process was figuring out how to get the material streaming. Each film was in a different state of digitization and many of the filmmakers we reached out to who are not in the series were unable to get to materials that were locked away, inaccessible, in offices at universities or archives. We were really only able to work with films that were either in, or could be relatively easily transferred to, digital form. For example, we had to rip a DVD in order to get the digital version of Terminal USA (Jon Moritsugu, 1993) and, after an international search for a digital file, we ended up getting Twitch (Amit Desai, 1999) transferred from mini-dv to digital in a transfer house deep in Brooklyn that is still open for business. It’s actually been a real adventure. The improvisational nature of the process has kept a certain looseness and lightness in the program and our internal/external communications. This is definitely a passion project. Abby did a lot of research on different syllabi and past programming as well which helped us discover filmmakers we weren’t familiar with and identify gaps. Zach Vanes at VDB also suggested some titles once he understood what we were going for. It has all been very collaborative.

AS: There were several recent texts that helped orient my deep dive. First, and really foremost, reading Jun Okada’s Making Asian American Film when it was published a few years ago was the first time I encountered an explanation of the institutional history of Asian American film. That book has an entire chapter on Terminal USA for instance, and also situates Strawberry Fields amongst its “Class of ‘97” contemporaries in a thoughtful way (against the onset of globalized film production). It connected a lot of dots for me about how things became the way they were, with this focus on critical success that can’t be separated from commercial profit in mainstream Asian American cinema like The Farewell (Lulu Wang, 2019) or Crazy Rich Asians (Jon M. Chu, 2018). Since discovering Okada’s book, I’ve been able to talk to industry stalwarts like Don Young at CAAM who have also helped orient me to this history and to changes in the industry.

I had also learned quite a bit from co-organizing a roundtable for Film Quarterly’s special dossier on Asian American film, just recently released a couple months ago. In that issue, this roundtable was the only piece to address more experimental work and that was how I got to interact with Rea, Roddy and Shu Lea. So when Keisha called and dropped their names, I immediately understood her positionality. Also, through the Film Quarterly issue, I became really interested in Kelly Loves Tony (Spencer Nakasako, 1998) because of its unique edit structure, to the point where, out of all three of his “refugee trilogy” films, we picked the one that is often overlooked in favor of the Emmy-winning a.k.a. Don Bonus (Spencer Nakasako, 1995).

Through Okada’s book, I inferred that there was contemporaneous coverage of certain Asian American film festivals. I also knew, from having attended Asian film festivals as a programmer and writer, that a lot of them do large non-competitive showcases of Asian filmmakers, and since they really understand the transnational diasporic spread of Asians across the world, those programs were always inclusive of work being made in the US. Yamagata [International Documentary Film Festival]’s pioneering New Asian Currents program is a highlight of this in the documentary world, and their website is also a complete archive. So I looked up old festival catalogs, and in cases where I couldn’t find them online, I looked up newspaper reviews covering the festivals and gallery shows. For instance, I discovered that New Yorker staff writer Hua Hsu covered the San Francisco International Asian American Film Festival for tiny local (Chinatown) papers as a college student! Museums like MoMA had a few shows centered around groups like Indian American video makers. Back issues of journals like Jump Cut provided both titles and contextualized them. And after indieWire was founded and really up and running in the late 90s, its archives are, whatever you think about the site, extant and super accessible for researching what was being programmed and how they were received. We also found college syllabi, though they are less useful than one would think—most classes focus on media analysis and theory, and so contain films about Asian Americans more than films by Asian Americans, and even if they are weighted towards the latter, most skip over more experimental films.

All of this research also helped me edit the essays we commissioned. This is a history that, for writers who started working more recently, is often unknown beyond the surface-level knowledge from oral histories of Better Luck Tomorrow (Justin Lin, 2002) and The Joy Luck Club (Wayne Wang, 1993) that popped up during the Crazy Rich Asians release.

I also want to shout out archives like VDB, WMM and Vtape who digitized some of the videos we asked for. But above all, we have to thank the filmmakers a lot, though, and especially filmmakers like Gina Kim and Kimi Takesue, to just name two, who don’t have any films in this program—they did the same tedious work of digging through hard drives and trying to locate files during COVID-19 lockdowns.

Thinking about My Sight is Lined with Visions as an online project, what did you do differently in programming, organizing and producing it than you would have for a screening series in a cinema? What challenges and opportunities did you encounter with taking this program online?

KK: We took quite a bit of time to think about what the value of an online screening series of these films could be. It was very important to us that there were many different ways to engage with the program and that it was generating new knowledge, engagement and potentially even relationships. It was also very important to us that during COVID-19 price wouldn’t be a barrier. We came up with a two-tiered pricing system so the audience can pay a higher or lower fee depending on what they can afford. Even then, we wanted to make sure that people could have something to view free of charge. Our free screening section, The Vault, grew out of this. The Q&As and the essays are also things people can engage with without a paywall. In a way, the online format allowed us a certain flexibility and the ability to create something substantial with a minimal budget. It’s also the particular circumstances of our current home-based realities that made us feel the time was right to get eyes on these films. In a more distracted moment in time it might be more difficult to get people engaged with an online repertory series aimed at discovery like ours is. Of course many of the films we’re showing are available as prints and it would have been great to show the films in this way. That said, this virtual cinematic environment really allows us to create an international community of viewers which is extremely exciting!

AS: Film culture is more internet-native and -resilient than it appears, with the holy grail of photochemical film and the black box theater with its magnificent screens. For one, I grew up in the middle of the US, without access to what is traditionally thought of as cinema culture (though eventually Ragtag Cinema and True/False Film Fest came along, and I later returned to Columbia, Missouri to program for both). It was past the heyday of college film societies and so I watched movies from the grocery store VHS rental section, in multiplexes and on the internet (IMDb message boards and online forums) by—I’m going to just say this—torrenting movies.

To return to Keisha’s points about the work handling the (digital) material—we knew from the beginning that access to digital masters was going to be difficult, and we would have to deal with a loss in image fidelity. I suspect this is one reason why not many other non-institutional independent series have gotten off the ground. Many of these filmmakers have copies of their files in a locked university office or in a storage unit while being stuck outside the country as most borders were closed for all of last month. Interestingly enough, we watched one of the films through an unauthorized/pirated upload to Youtube, with the filmmakers’ blessing to do so. (They have since filed a copyright claim against this upload and Youtube took it down, so I suppose our series provided an impetus to do this.)

On the upside, this allows us to have faith in many of the digital offerings of this series, which are geared specifically towards an online existence. Not printing programs means that we could pour our limited resources into commissioning the essays. Downloading already-uploaded files, even through accessing the accounts with the filmmakers’ own logins, means we start out with already-compressed files before our own uploads, but also means that we are disturbing the supposed perfect replicability of digital and inscribing a sense of how the films got there. As Keisha says, it’s the digital glitch as film scratch. It means that we were always going to favor the stream-anytime strategy over live streaming films, and that handling online Q&As and mirroring live streams was something that we’d already tried before and could tack on fearlessly. It also means, in the structure of the Q&As, that we’ll be borrowing from Instagram and Facebook livestreams more than from a traditional panel.

Other than the vastly expanded potential audience, limited only but still significantly by internet access, I don’t know if we could have put together this program at all, and on such a short notice, if it weren’t online. Otherwise we’d have to secure a venue, negotiate a split with the theater so they could cover labor and lost revenue, spend money on shipping DCPs and prints, think about how we would fly in filmmakers if we wanted to do a group discussion instead of Skype-in post-screening individual conversations, and embark on a tour across cinemas if we didn’t want to limit it to Boston (where we both live) or a more conventional market like New York. It can be enormously rewarding to secure institutional and community support in that way. Indeed, in-person screenings are experiences to which both of us have dedicated our lives. Perhaps this is something we can still do in the future. But not everyone has the privilege of encountering films in a theater.

In previewing several of the films in the series, I definitely got the impression of how, as Abby put it, “gloriously messy and punk Asian American film really can be.” I saw body horror, tribal humanoid mating rituals and a gloriously maladjusted family portrait. To finish, I wonder if you might each highlight a film or two that you think are particularly effective in pushing the envelope and using subversive content or form in conveying the filmmaker’s message or vision.

AS & KK: We really feel committed to the collectivity of this endeavor and personally feel like all of the films, painstakingly chosen, are each the best! The idea of the series is exploration and we don't want to taint our audiences experiences even though we couldn't because we truly love all of the features and shorts. What about a haiku instead?

In Summer the warm comes

A union of sight and sound

Making space new here

Endnotes

Thank you to Abby Sun & Keisha Knight for speaking with me and especially for that excellent haiku. Once again, My Sight is Lined with Visions is online at Sentient.Art.Film’s website from May 29–June 7.

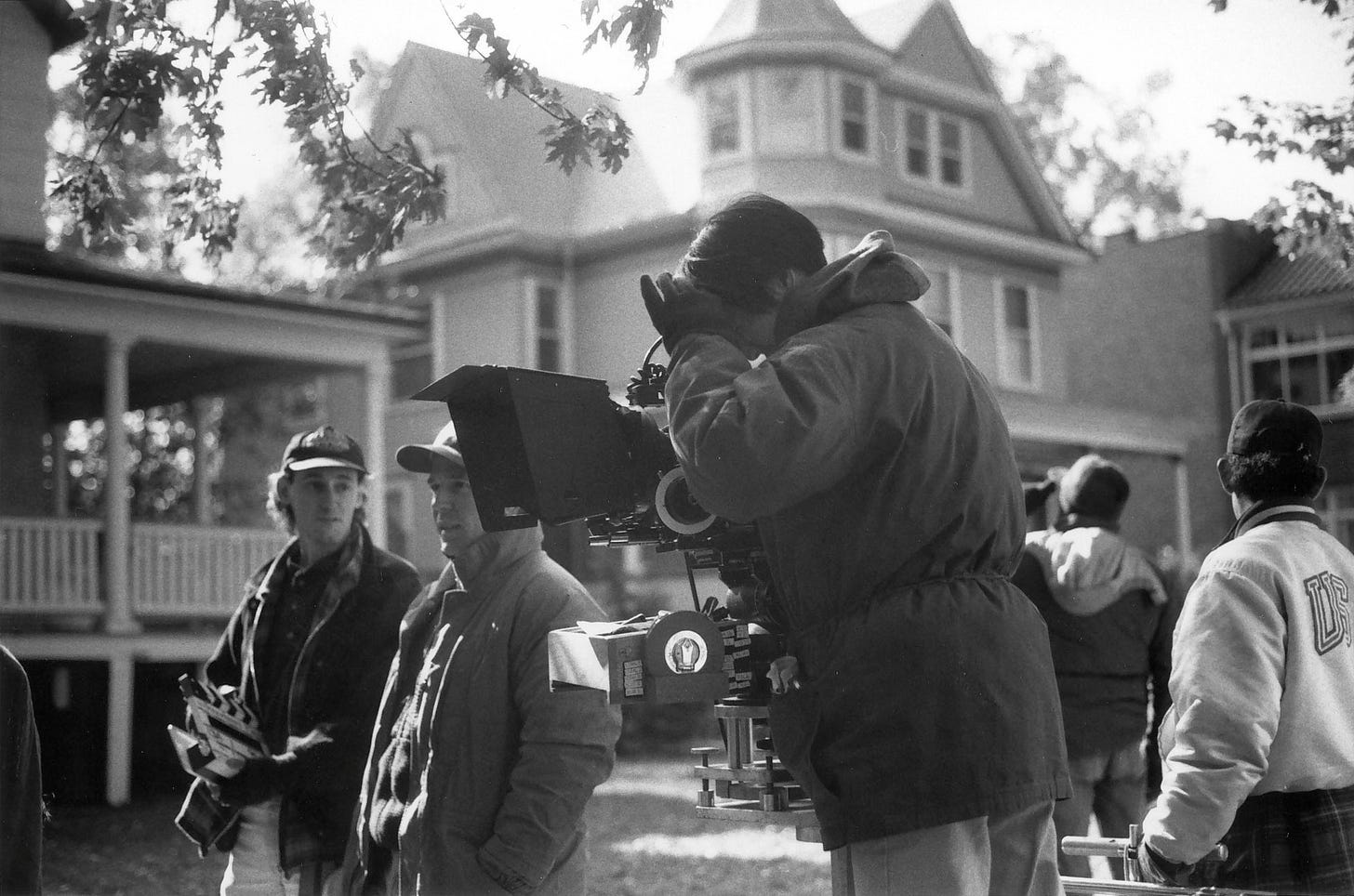

Images: Terminal USA (Jon Moritsugu, 1993, US) // Kore (Tran T. Kim-Trang, 1994, US, image courtesy of the Video Data Bank at the School of Art Institute of Chicago) // Sally’s Beauty Spot (Helen Lee, 1990, Canada/US) // Rea Tajiri shooting Strawberry Fields (1997, US)

In the works: a new podcast, interviews and so on. Stay tuned.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe if you’re coming to this from the website and please share if you find this useful. While the main channel is this Substack newsletter, you can also find Rep Cinema International on Twitter, Instagram and in list form on Letterboxd.

Questions, comments or other inquiries: RepCinemaInternational@gmail.com

Yes won't samthing extra letest new idias would were were fast like work I am spesial work one day in world femash won't this work.